The Sacrifice of the Son of God

by ALEX HALLAnd Samson said to the lad that held him by the hand, “Help me to feel the pillars which hold up the building, so that I may lean on them” (Judges 16:26).

Assumptions are insidious, being by their very nature things which we do not realize we are making. It is only by uncovering and interrogating them that dialogue around issues of faith can move beyond “proof-texting.” For true progress to be achieved some attempt must be made to identify, address and question the common themes, or systems of thinking — the term paradigm might be appropriate — which determine the lens through which a person reads a text in the first place. It is these structures which dictate the arrangement into which the many beloved “refrigerator verses” are placed and the sense which is made of them. Yet too often the structure itself is not examined closely enough to determine whether or not it has any basis in Scripture. The cart, so to speak, is put before the horse.

It seems to me that there are two principal pillars, or dominant preconceptions, upon which the whole Trinitarian edifice leans. If one of them is the conviction that Jesus must ontologically be God because he acted so much like God, then a strong contender for the title of second pillar would be the assumption that Jesus had to be God Almighty in order for him to have been able to secure our forgiveness. It is the aim of this article to attempt to feel for the shape of this pillar and, possibly, give it a good shake.

Without wanting to appear dismissive, I have to state at the outset that it appears to me, and not for want of searching, that there is no clear statement in the Bible to this effect. Instead, what we do find in those passages which deal with Jesus’ “qualification” to be our ransom sacrifice is the unambiguous assertion of factors related to his humanity — the necessity of his relation to Adam and, by extension, those descendants of Adam whom it was his mission to redeem.

Before we explore this further it may be fruitful to consider the ground on which the pillar stands — the historical circumstances which gave rise to this assumption in the first place. Perhaps this may contribute some insight into the powerful hold it exerts upon the convictions of so many believers to this day.

Relating Jesus’ nature to the issue of salvation necessarily raises concerns that go beyond Christology and into soteriology. This calls for an inquiry into what the Bible has to tell us about what it means to be “saved.”

In the early post-apostolic Christian communities the influence of pagan Greek thought on the Jewish faith had given rise to a divergence of opinion on this subject. An attempted shotgun marriage between Greek presuppositions and the witness of the Hebrew Bible and New Testament documents spawned a new, dualistic, soteriological outlook. According to this framework, “matter,” the material, physical world per se, was the problem. It was presented as being so deeply corrupted by sin as to be intrinsically evil. This was contrasted with the realm of “spirit” which was intrinsically good. To this novel idea they bolted on the Genesis account of Adam’s act of disobedience and, in so doing, secured for themselves the apparent support of a scriptural narrative for the origins of their innovation. “Thus there arose a new doctrine of Christ’s work of Redemption, which differed in its structure from that of the original Apostles and Paul.”1

To this perceived predicament two competing solutions were put forward.

One, championed by many of the more influential Gnostic schools, held that the situation was beyond hope and the only available remaining course of action available to God was to scrap the entire creation project. Only that part of the person which is spirit could be salvaged. Everything else would have to be destroyed. “For Gnosticism Redemption meant the emancipation of the spirit from the substance of the physical body.”2

The second concept of salvation which relied upon this dualistic cosmology was put forward by the movement which was destined to inherit the title

“orthodoxy.” This perspective posited the redemption of matter by means of its being reunited with, what to them, was the essence of that which is spirit — God.

And the locus of that union was the event at which the essence of divine spirit became joined with material flesh — the moment God became a man. Becoming incarnate in the human body of Jesus, the eternal Logos3 had restored the entire material realm by encompassing it in a sort of redeeming embrace. “The divine Logos effects the reconciliation by establishing the essential union4 of God and Man.”5

In this context a surprising discovery presents itself. Instead of the assertion that Jesus had to be God to effectively deal with sin having arisen from the need to defend an incarnation Christology, the opposite is actually the case. It was to meet the soteriological demands of a dualistic cosmology that the incarnation of God in human form was presented as a resolution. “The formation of a new doctrine of Christ’s work of redemption... in turn involved a new doctrine of his person.”6

More than that: According to Martin Werner it was the new doctrine’s apparent ability to answer this vexed, though entirely novel question, which gave it such persuasive force in the midst of a generation who had lost touch with the original biblical salvation narrative. The original New Testament doctrine of redemption was unable to compete with its rivals on their home ground since it did not provide a resolution to the problem of salvation perceived in dualistic terms.

It was in fact possible to present this doctrine in a completely intelligible manner, without reference to the originally fundamental eschatological dogma of the soteriological significance of the Death and Resurrection of Jesus. By speculating about the soteriological significance of the Incarnation of the Divine Logos, Hellenistic Christianity abandoned completely the ground of the original Apostolic faith and built on what was, from the doctrinal point of view, virtually new land.7

Some evidence of the prominence which this teaching acquired is found in its achievement of creedal status, demonstrating that it had attained recognition as definitive dogma in the orthodox church.8

The implications of this process for the relationship between Orthodoxy and Gnosticism are important. In an important aspect of Christian faith Orthodoxy championed a view which was antithetical to Gnosticism, but based upon the same fundamental presuppositions. This situation could be compared to two people climbing up different ladders, all the while soundly cursing one another for it, but not realizing that both ladders are leaning against the same building.

According to the original biblical account the creation was declared to be good in the beginning9 thought it has been temporarily subjected to futility as the result of the disobedience of its appointed custodians, the human race (Rom. 8:20-22). This situation is destined to continue until the great renewal takes place and the heavens and earth are transformed and joined together to become the fitting inheritance for a new, mature humanity of which the resurrected Jesus is the forerunner (Isa. 66:17, 22; Rev. 21:1-5).

The issue at stake, therefore, begins and ends with the damaged relationship between humanity and God which is the result of disobedience. In the context of both the New Testament and its source document the Hebrew Bible, salvation is not a question of a cosmological predicament in which human beings are trapped, and to which a cosmological solution is needed. Rather it is in its essence a human, relational problem requiring a resolution on the plane of divine-human relationships. According to this model a savior is needed who is closely related enough to Adam to be able to recapitulate his story, succeeding where he failed.

Only in this way would sin be defeated on its home ground, and disobedience and rebellion overthrown. By means of a radical covenant faithfulness lived out, the servant of Yahweh was to personally fulfill God’s new contract/testament with humanity as their representative.

Notice how the locus of the saving act is entirely different in the two schemes. In the former it is the reconciliation of cosmic forces that takes center stage and the human aspect, though present, is marginal. In the latter it is absolutely central. The entire issue from beginning to end hinges on the relationship of human beings to God, with the material world participating in the consequences as an effect.

But it was the New Testament’s very fidelity to the original Jewish narrative that limited its sphere of influence with the masses, on account of the fact that their minds had been molded by Greek thought-forms. The inability of the biblical doctrine of Christ’s saving work to answer a new question undermined the credibility of a Christology which posited a Jesus who was “merely human”

and not the product of an intermingling of divine spirit with fleshly matter. To effect the reconciliation of two spheres the Greek perception of what it means to be saved demanded a divine-human being. In order to find acceptance within this framework, Jesus had to be both God and man. A wrong prescription had been issued, based upon a mistaken diagnosis as to the true nature of the ailment.

Up to this point the New Testament’s teaching has been discussed in general terms. It may be appropriate to turn our attention now to the most important passages and consider them in a little more detail. There are three.

| Romans 5:6-19 6 For we yet being without strength, in due time Christ died for the ungodly. 7 For one will with difficulty die for a righteous one, yet perhaps one would even dare to die for a good one. 8 But God commends His love toward us in that while we were yet sinners Christ died for us. 9 Much more then, being now justified by His blood, we shall be saved from wrath through Him. 10 For if when we were enemies, we were reconciled to God through the death of His Son, much more, being reconciled, we shall be saved by His life. 11 And not only so, but we also rejoice in God through our Lord Jesus Christ, by whom we have now received the reconciliation. 12 Therefore, even as through one man sin entered into the world, and death by sin, and so death passed on all men inasmuch as all sinned: 13 for until the Law sin was in the world, but sin is not imputed when there is no law. 14 But death reigned from Adam to Moses, even over those who had not sinned in the likeness of the transgression of Adam, who is the type of Him who was to come; 15 but the free gift shall not be also like the offense. For if by the offense of the one many died, much more the grace of God, and the gift in grace; which is of the one man, Jesus Christ, abounded to many. 16 And the free gift shall not be as by one having sinned; (for indeed the judgment was of one to condemnation, but the free gift is of many offenses to justification. 17 For if by one man's offense death reigned by one, much more they who receive abundance of grace and the gift of righteousness shall reign in life by One, Jesus Christ.) 18 Therefore as by one offense sentence came on all men to condemnation even so by the righteousness of One the free gift came to all men to justification of life. 19 For as by one man's disobedience many were made sinners, so by theobedience of One shall many be made righteous. | 8 God and Christ are clearly distinguished here. Why didn't Paul just say, "God commends His love toward us in that while we were yet sinners He died for us"? 10 God/Son distinction. Again, wouldn't it have been more "Incarnational" of Paul to say, "If when we were enemies, we were reconciled to God through His death"? 12 The problem originates through one man and affects all men, and according to verse 15 the grace of God comes by means of one man, Jesus the Messiah. 15 Adam was not divine though he had divine parentage, being a direct creation of God. Why shouldn't the same condition be sufficient to qualify Jesus? 19 There is a perfect correspondence here. For the offense of a disobedient man reconciliation is effected by means of the righteousness of an obedient man. |

| 1 Corinthians 15:21-22 21 For since death is through man, the resurrection of the dead also is through a man. 22 For as in Adam all die, even so in Christ all will be made alive. | Note the symmetry. The story of sin and salvation is that of two men. The first fails and the second is the hero who brings the solution. |

| Hebrews 2:11-12, 14, 17 11 For both He who sanctifies and they who are sanctified are all of One, for which cause He is not ashamed to call them brothers, 12 saying, "I will declare Your name to My brothers; in the midst of the assembly I will sing praise to You." ... 14 Since then the children have partaken of flesh and blood, He also Himself likewise partook of the same; that through death He might destroy him who had the power of death (that is, the Devid), ... 17 Therefore in all things it was suitable for him to be made like His brothers, that He might be a merciful and faithful high priest in things pertaining to God, to make propitiation for the sins of His people. 18 For in that He Himself has suffered, having been tempted, He is able to rescue those who have been tempted. | 11 This is the theme of the entire passage. Jesus' priestly offering of himself is based upon the closest possible relation of himself (being "all of one") to those who he has been raised up to save -- his "brothers." This relationship is jeopardized by the assertion that Jesus is God in human form, and is only strengthened by being released from it. 14 Qualification -- to be a partaker of flesh and blood. To be mortal. Victory through death -- the immortal God cannot die. More on this later. 17 Which one of his brothers is God incarnate? 18 As for the suffering of temptation: "God is not tempted by evil" (James 1:13) |

Not only is there is no hint at an insistence that Jesus had to be God in order to atone for our sins anywhere in the New Testament, it is also absent in the three places where we should most expect to find it, namely those passages which deal with Jesus’ qualification as our atoning sacrifice. It seems to have been enough for the writers of the New Testament for Jesus to have been human.

One inevitable consequence of this incarnation soteriology was a shift in emphasis away from the words and deeds of the historical Jesus. Salvation had been secured, so to speak, from the gate. Everything Jesus subsequently said or did would simply be an afterthought since, in Werner’s words, “In principle the divinization of the physical body of Man was effected in the Incarnation of the divine Logos.”10

To put it differently, one salvation scheme is based on what Jesus did, the other on who he was — and that from his conception. Seen from this perspective even the resurrection is demoted to the position of an afterthought. Instead of being Jesus’ reward for his obedience to the plan of his God and Father, it is merely a manifestation of the divinity which he had possessed all along. God had become a man and everything else was just icing on the cake. “The difference lay in the fact that the new doctrine assigned a primary constitutive significance to the Incarnation of the Logos in contradistinction to his Death and Resurrection.”11

But, as we have noted above, the recurrent Adam Christology of the New Testament locates the origin of the sin-problem in what Adam did — his act of disobedience — not what or who he was. And the solution which the New Testament sets out is entirely consistent with this appraisal of the situation. It is based upon a man who effects reconciliation by what he does.

Hence we find the gospel passion narratives steeped in Edenic imagery in a way entirely consistent with the Adam Christology of the epistles. Jesus is unmistakably presented as recapitulating the tragic events in Eden. For example, just as it is in a garden that the first Adam rebels, it is also the place where Jesus, in agony, surrenders his will to the Father’s. As a result, the thorns which constitute the Adamic curse become his crown and, of course, at the heart of both stories there is the tree. Embracing the full consequence of Adam’s taking the forbidden fruit from the tree, Jesus is nailed to the wood of the cross.

Throughout, his story is Adam’s story, the negative having been inverted into a positive, albeit gruesome, picture.

The New Testament gives a Christology in two stages. It was not enough for Jesus just to be created the innocent, mortal, chosen and empowered Son of God.

He was given a mission to fulfill and a Gospel to preach. Had he not done so he would have failed in his calling to bring salvation to humanity. It was only subsequent to his mission and sacrifice that he became the Son of God in power by the resurrection from death to imperishable life (Rom. 1:3-4; Phil. 2:5-11).

In giving due emphasis to the Gospel about the kingdom of God, Abrahamics must at all costs be careful that our insistence on the future consummation of our salvation not come at the expense of the vitally important Gospel truth of Calvary and the empty tomb. It must not be reduced to something we merely give a nod to in order to avoid giving offense to evangelicals. We must value, love and stand in awe of what Jesus did as much as anyone.

But it is interesting to note the development of the orthodox position on this point. Today it is asserted that Jesus had to be God in order for his sacrifice to be sufficient to secure our forgiveness. An assertion which in its original form removed value from the death of Jesus is now, it is insisted, an indispensable aspect of it.

Let’s return for a moment to the garden and consider carefully what took place there. Was Jesus completely human? For him to be so must he have needed to be a complete man? Why ask such questions? Because if the humanity of Jesus is asserted, as it is in every “orthodox” creed, some clarity is needed as to what is meant by the term “human being.” This shouldn’t be too difficult since, for all our differences, we each have a lifetime’s experience of this. But it is important to ensure that our Christology, the language we use in describing Jesus as Messiah, matches up to it. If it does not we have fallen into docetism — a view which reduces Jesus’ humanity to nothing more than an outward appearance. Or, to use less technical terms, is it really such a dreadful splitting of hairs to question the assertion that “Jesus is a human being just like we are and Adam was…except for the fact that he was the eternal God and we aren’t”?

How does the relationship between God and Jesus, described as “God in Christ,” actually work? In the words of J.A.T. Robinson, “Is it effected by God’s joining a second (human) nature to his own, or is it by his using, acting through, a man? Is it, in a phrase, by taking manhood or by taking a man?”12

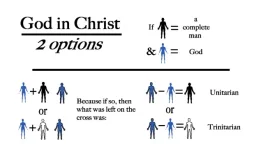

Was the Son of God merely a human body which God had prepared for Himself to dwell in? If so then did God’s own personality come to occupy the place where the man’s personal center would have been? Or else was a complete human being created who like every other human being had an autonomous selfhood of his own — an independent will? If so, then Jesus and God are two distinct individuals, however close their relationship. The first is a complete man and the second the God who inhabits him. The choice here is between a “flesh-bearing God” ( theos sarkophoros) and a “God-bearing man” ( anthropos theophoros).

If Jesus and his God are ontologically one the biblical scheme of Jesus’ exemplary surrender to the will of God breaks down. The will which is surrendered to God is in actual fact God’s, and the man offering himself to God is in reality no less God than the God to whom he prays. God, in the guise of a man is, in reality, simply submitting to his own self. The proposition that, in Christ, God called forth an obedient response from humanity is called seriously into question if what really took place was a matter either of God trusting and submitting to himself, or one part of God doing so to another. For a person to will what God wills, an essential prerequisite must be that they have a will of their own to offer in the first place!

The most complete, the fullest, the most organic and integrated union of Godhead and manhood which is conceivable is precisely one in which by gracious indwelling of God in man and by manhood’s free response in surrender and love, there is established a relationship which is neither accidental nor incidental, on the one hand, nor mechanical and physical on the other; but a full, free, gracious unity of the two in Jesus Christ, who is both the farthest reach of God the Word into the life of man and also (and by consequence) the richest response of man to God.13

On this basis, the author goes on to comment that for a person to do the will of God, “to be fully and independently a man is a qualification, not a disqualification.” Ontological identity between God and Jesus serves only to undermine the validity of what the Bible clearly tells us about both.

Another issue which brings us to the heart of this question, perhaps helping us to take a firmer grip of the pillar, is the question as to the scale of what God offered. It is a common assumption that if what God really offered in the person of His Son was His own self, then, God being infinite, His sacrifice would be of infinite value, nothing to be compared to the offering of a “mere man.” Let’s examine this a little more closely. To begin with there is the fundamental contradiction inherent in the assertion that the immortal God, who cannot die, actually did. At the very least, on this basis it must be conceded that only the human, and not the divine, part of “God-the-Son” died, so Jesus did not give all of himself. But, leaving that aside, who or what is it exactly that God sacrificed on the cross? This question retraces our steps, moving back from soteriology into Christology and our “hollow man” diagram.

Jesus’ cry of dereliction on the cross “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” effectively focuses the question we asked earlier. If we remove God from Jesus, what is left? A man, independent of God, or something less? If Jesus is anything less than a complete man, distinct from the God who created and indwelt him, then when God forsook His Son on the cross, all he did was shed a body and return to heaven. The Son’s cry of dereliction is reduced to the mere amputation of a temporary shell inhabited by the eternal God.

According to the orthodox father Hippolytus, this could be compared to God removing an item of clothing he had chosen to wear: “The logos, as a bridegroom, had woven for himself a garment out of the holy flesh of the holy Virgin.” To which Werner comments, “[the logos] used the holy flesh of the Virgin as an outward covering. This ‘garment’ was the human physical body, indwelt by him, which became immortal, because it was ‘compounded’ of the Spirit of the Logos and the physical substance of Man, i.e. of the immortal and the mortal.”14

But if Jesus is a complete human being in addition to the indwelling God, then both he and God gave much, much more. God actually gave His own beloved Son in exchange for us. This is an act of sacrificial love the scale of which lies beyond the power of human comprehension. And the man Jesus gave up everything he was.

But what about the Trinitarian doctrine that there is a distinction of persons within the Godhead? Perhaps this may account for Jesus’ words in a way which does justice to his divinity without reducing him to being a docetic hollow man.

In connection with this it is important to note what Jesus did not say. He did not say “my Father, my Father” but “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”

Here Jesus reveals himself to be not only someone other than the Father, which the Trinitarian model freely concedes. He is also someone other than God. And, according to orthodoxy, the divine substance shared by both Father and Son is the very basis of their ontological union. In one utterance Jesus uproots the carefully crafted and much disputed pivotal homoousian element of the Trinitarian formula depicted in the diagram below.

Only a “merely” human Jesus could give up everything he is, completely offering his whole self, pouring out his soul to death. Only for him could that surrender be a genuine step of faith,15 into the unknown, as opposed to the return to a prior state of existence in a far better place than the troubled streets of an occupied land. On this basis I would suggest that the Trinitarian Jesus actually sacrificed less, since it was only his body that died — the material, mortal part of himself, which he assumed at his “Incarnation.” He was already a complete “divine person” before his conception and presumably continued to be so throughout the death and resurrection of his bodily shell.

Conclusion

The impulse which gave rise to the insistence that Jesus had to be God in order for his sacrifice for our sins to be sufficient, arose from a set of cosmological concerns which are entirely alien to both the Hebrew Bible and 15 In Gal. 2:20 Paul speaks of “the faith of the Son of God.”

New Testament. In spite of the fact that the current view is something of a more moderate residue of this and does assign due emphasis to the significance of Christ’s sacrificial work on the cross, nevertheless the continuing insistence that Jesus had to be God in order to do this is incompatible with the framework provided for us by the New Testament and does violence to its fabric.

1 M. Werner, The Formation of Christian Dogma, A. & C. Black, 1957, 194.

2 Ibid., 195.

3 Understood by them to be a personal spirit-being as opposed to God’s creative blueprint and effectual utterance.

4 With the term “union” being understood by them ontologically, as opposed to covenantally.

5 Werner, 197.

6 Ibid., 193.

7 Ibid., 194.

8 As witnessed in Irenaeus, Adv. Haer, V, 16, 3.

9 Genesis 1:10, 12, 18, 21, 31.

10 Werner, 193.

11 Ibid., 194.

12 J.A.T. Robinson, The Human Face of God, Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1973, 197.

13 W. Norman Pittenger, The Word Incarnate, Nisbet, 1959, 188.

14 Werner, 195.